But while Carver perhaps lacked the imaginative exuberance, and early educational opportunities, of a Barthelme, his fiction gave readers something they craved, maybe without even knowing it. A Publisher’s Weekly reviewer of the first collection noted that Carver voiced the “inarticulate worlds of Americans,” the dim ache in the nondescript lives of aspiring students, down-and-outers, diner waitresses, salesmen, and unhappily hitched blue-collar couples. Carver’s approach to quiet desperation is poetic, eschewing flashy postmodernist contraptions for powerfully direct and evocative images. As: The Carveresque image allows the reader to glimpse the terrible waste of his characters' lives (something the characters themselves can sometimes feel but rarely see) and forces the reader to reconsider the entire story in the image's dark light.

In the audio at the top, you can hear Carver’s friend, writer Richard Ford, read “The Student’s Wife,” from Will You Please Be Quiet Please?, as part of. Ford describes the story as “spare, direct, rarely polysyllabic, restrained, intense, never melodramatic, and real-sounding while being obviously literary in intent.”. Carver, a man of self-destructive appetites, understood the craving of characters like Rita, the waitress in “Fat.” His own desires drove an alcoholism that nearly killed him. Several of his characters share this flaw, including Wes in Carver’s story “Chef’s House,” read above by celebrated short story-ist. Published in The New Yorker in 1981, '” marks the beginning of Carver’s long relationship with the tony magazine. In 2007, The New Yorker also, inspiration to thousands of creative writing students, by showing how his streamlined prose was perhaps as much the product of Alfred A.

They’re Not Your Husband by Raymond Carver 3 Jan 2014 Dermot Will You Please Be Quiet, Please Cite Post In They’re Not Your Husband by Raymond Carver we have the theme of embarrassment, appearance, acceptance, control, obsession, selfishness and insecurity.

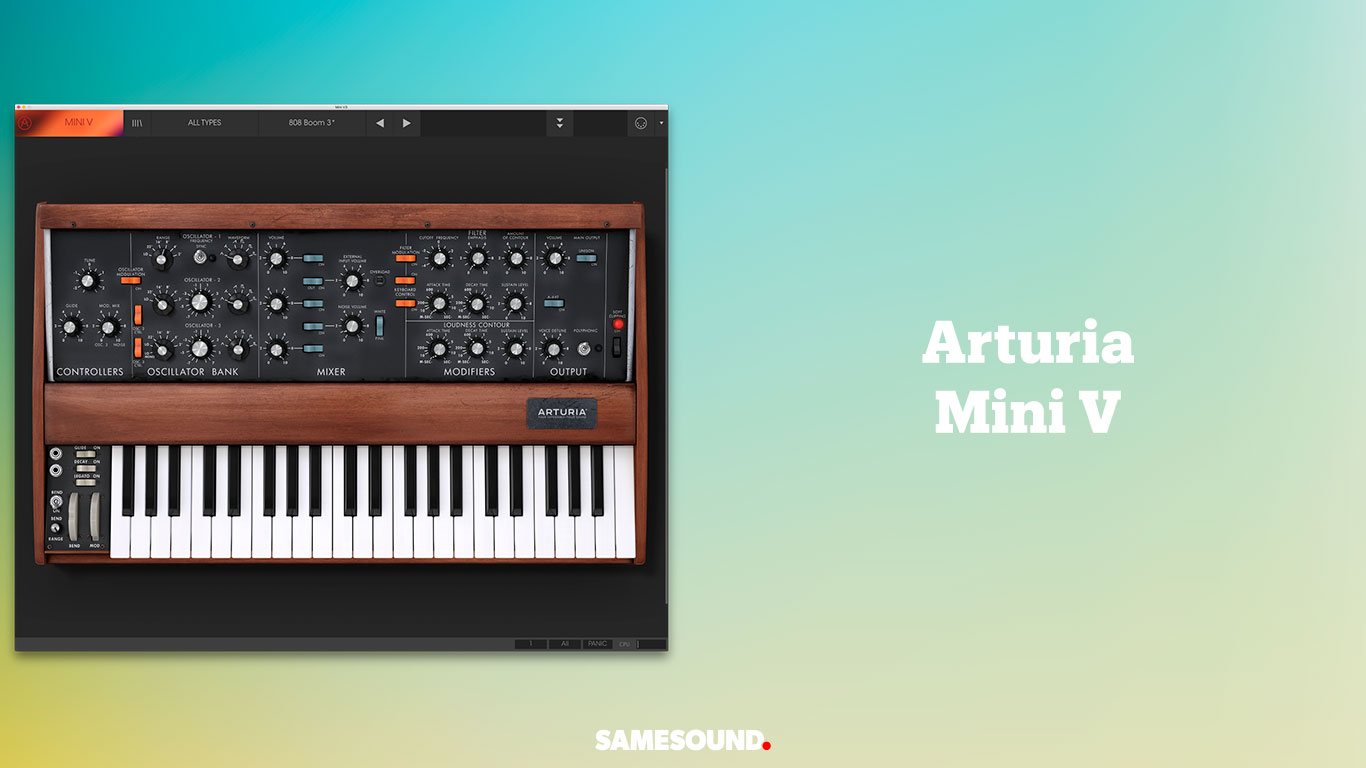

Unfortunately there is no on-board sequencer.

In a system created by Putin, it is only possible for Putin to win. I am realistic about who will become the president.' Pechenje cherez myasorubku so smetanoj. Under current Russian law, Putin may not run for President for a third consecutive term in 2024, just as he was barred from running for President in 2008.

Knopf editor Gordon Lish as of the author. The magazine published which became in Lish's hands the signature story “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.” I do not think lovers of Carver need be too dismayed by these revelations. Several well-known works of literature are close collaborative efforts between editor and author. See, for example,, which we’d never know by that name without Ezra Pound (the famous footnotes ). And the glittering sentences of Fitzgerald would not shine so brightly without. But as The New Yorker alleges, Carver felt forced to accept Lish’s edits.

Once he had gained more confidence and success, his prose took on much more expansive qualities, as you can see in the 1983 story “.” The readings above can be otherwise found in our collection of. Related Content: Josh Jones is a writer, editor, and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness.

Raymond Carver wrote a prosy kind of poem. Which shouldn’t surprise us since prose is what his reputation mainly rests on.

He penned poems, it seems, when his short-story muscles needed a rest. And, like Walt Whitman, he did it almost entirely in free verse. A typical Carver poem consists of sentences and phrases arranged on the page to resemble poetry, but don’t bother trying to scan them. Some have found this off-putting.

Fred Chappell, writing in the Kenyon Review, once said of a collection of Carver’s verse, “It is difficult to think of these productions as poems; they stand in relation to poetry rather as iron ore does to a Giacometti sculpture.” That’s mean, but it’s easy enough to see where Chappell is coming from. Still, though, Carver’s poetry is not without interest. His best poems, and there are a number of pretty good ones, represent a triumph of content over technique, of feeling over method. Take, for instance, the little poem “Mother” in the collection Ultramarine, which begins, “My mother calls to wish me a Merry Christmas. / And to tell me if this snow keeps on / she intends to kill herself.” Now there’s an interesting opening—for a poem, or a piece of prose, or whatever. And it’s what Carver had going for him: an interesting life, a life out of the ordinary, something worth reporting on. Carver’s family—his wife, his kids, his feckless parents (his mother constantly threatening to kill herself)—were a treasure trove of material.